A migration story in the writing: Illustrating the past with artist Helga Elsner Torres

Like many foreign explorers and adventurers in the early 20th century, Elsner Torres’s paternal great-grandfather emigrated from Germany to Peru. He fathered a child and around the time his son turned five, he left and was never heard from again. The few stories that remain are those that have been passed down by four generations. Today, his great-granddaughter lives and works in Berlin. Through her latest artistic project “Wo kommst du her?” she opens the discourse about migration to all, asking: “Where do you come from?”

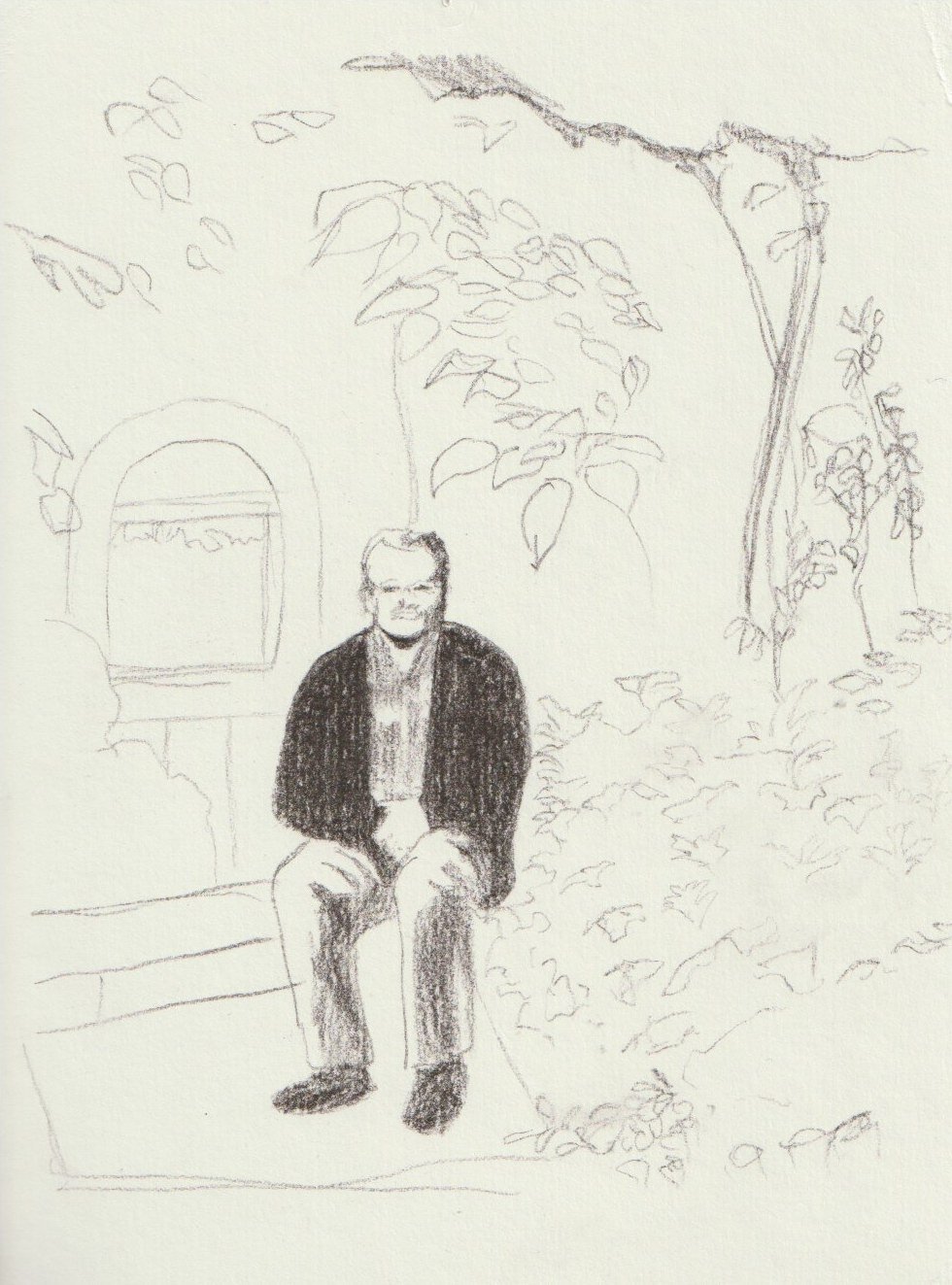

Helga Elsner Torres in her studio in Berlin, Germany. Photo taken by Peruvian Photographer and Documentalist Martín Rebaza Ponce de León (IG: @martin.rebaza).

Just as a second lockdown was announced and the grey cityscape of Berlin slid deeper into the late autumn months, already foreshadowing the shivering winter-cold that makes the city all the more gratifying, I met Helga Elsner Torres in her studio. While I was longing to return to the Peruvian summer, she appeared to be seemingly unshaken by the impending doom hanging over the city. Instead, she greeted me with a dignified composure that tells me that with five and half years under her belt, the young artist is very well accustomed to Berlin.

Aesthetics put aside, Helga Elsner Torres has a mission. In February of this year, she graduated with two scholarships from the largest European art school i.e. Universität der Künste (UdK). Since before completing her Master of Arts in “Kunst im Kontext” (“Art in Context”), her artistic articulations have always engaged with relevant societal discourses and taken into consideration their sociopolitical and -historical implications. When she lived and studied in Peru, she was particularly outspoken about the protection and our coexistence with the natural environment. Today her artistic development is fully dedicated to the transformation of her genealogical investigations - the study of her ancestral lines - into visual imageries that tell a story of migration.

The Peruvian artist lives and creates her art in an exciting and bustling neighbourhood that is known to attract young immigrants into the midst of a gentrified part of town. In Neukölln, you can find a vegan café alongside a kebab shop with an African grocer 50 meters further down the street. Migration waves to Berlin are common and some - minorities and majorities alike - are very well integrated into the trendy Berliner lifestyle, while others are encouraged by a series of grants and supporting foundations. The ‘Migra Up!’ (OASE Berlin e.V. & VIA e.V.) project, in its 6th year, is one such example, for which Helga, together with an international team, works as the Head of Public Relations in order to ensure the sustainable and lasting participation of self-initiated migrant organisations (MSOs) in their local district Pankow.

The German capital thrives off of its diversity and celebrates solidarity with its many communities. It has thus taken the young artist by surprise when, on multiple occasions, strangers would place her heritage at the center of their conversation. While their curiosities come with little ill intent, Helga has understood that the migration discourse patronises immigrants from less developed countries although the reverse is equally common. Everyone has some sort of migration background, yet most media portrayals narrate stories of loss and despair. Elsner Torres’s story is one of new-found meaning, purpose and the completion of her family’s narrative. Three to four times a week she retreats to her studio to sculpt or draw as a form of relaxation. It is then when her mind can travel: in time, up and down her family’s history; and in place, from Germany across the Atlantic to Peru and vice versa.

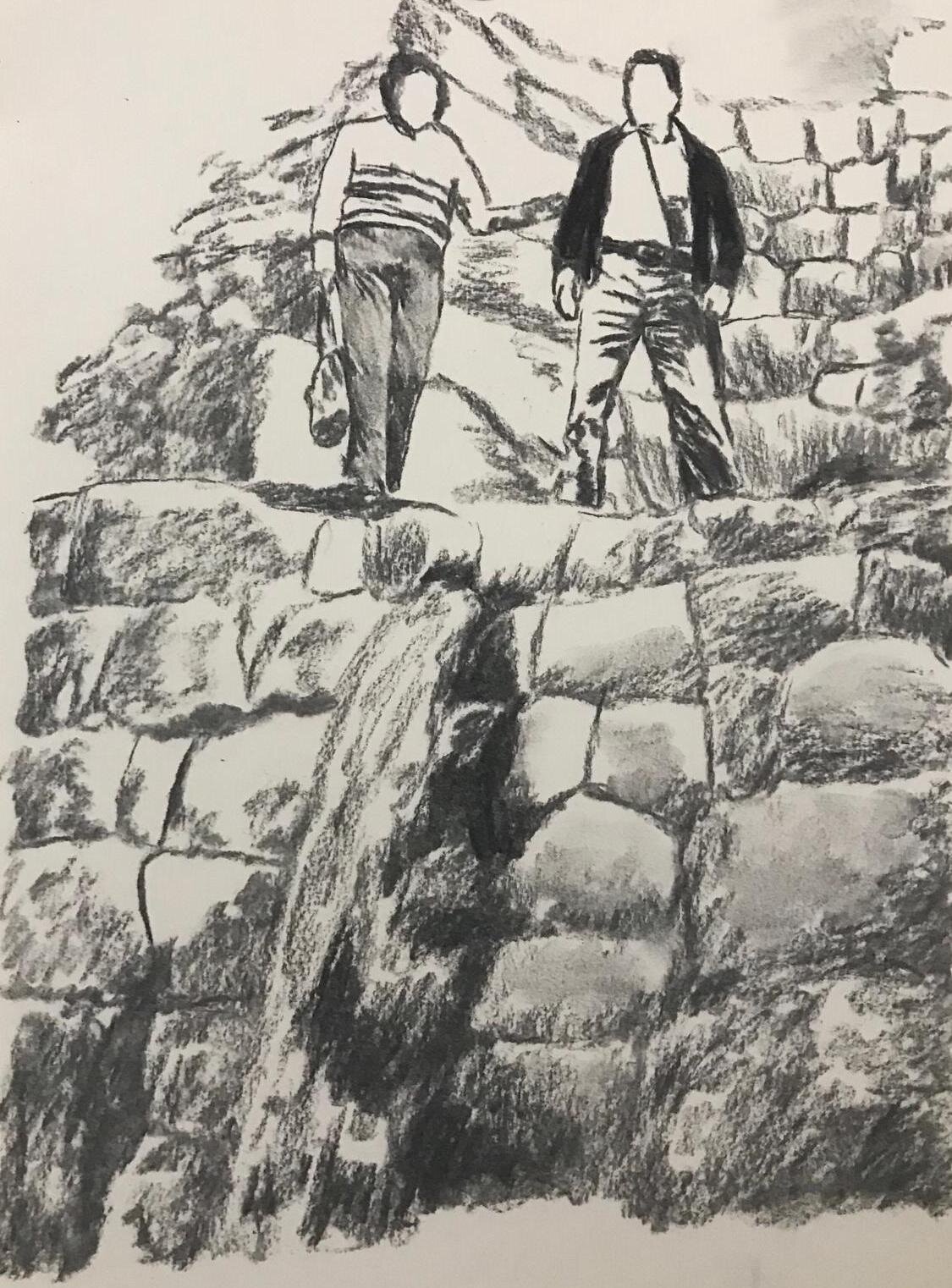

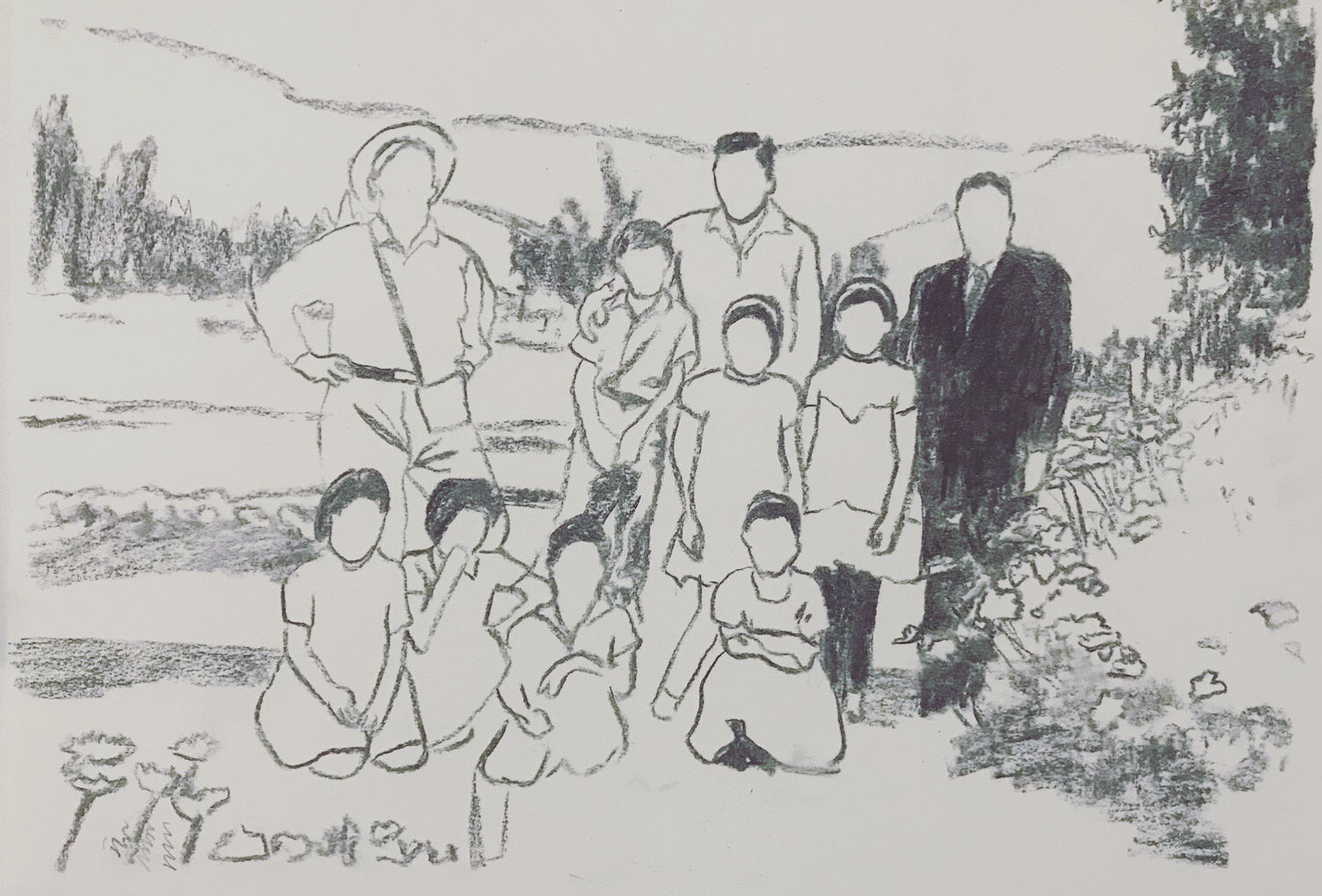

Photo by Martín Rebaza Ponce de León (IG: @martin.rebaza)

The mother’s ancestry runs through-and-through the northern San Martín region in the Peruvian Amazon rainforest. Although Helga spent her formative years living and studying in the Peruvian capital Lima, she regularly visited her relatives in the Amazonian city of Moyobamba. The demanding journey back-and-forth illuminated not only the infrastructural, but also the sociocultural and -political disconnect between the Andean and Amazonian states. Exposed to the maltreatment of local indigenous communities and the state-run mismanagement of their surrounding natural environment, Helga developed a vocal activist inclination at an early age.

In 2014, she conducted field work in the central region of the Amazon rainforest to document the detrimental effects of oil spills that had gone by largely unnoticed in (inter-)national news. Determined to make “tears in the system,” her intention was to bring awareness to the inaction of the common Peruvian in including and therefore improving the well-being of Amazonian communities. She was granted with special access to restricted areas in order to study the cause and effects of the numerous petroleum accidents and intervene limited media coverage. The research project was commissioned by the Tomás Saraceno Studio and made possible with the support of the Human Rights Commission of the Apostolic Vicariate of Iquitos, lawyers from Instituto de Defensa Legal, artists and sociologists.

The following multidisciplinary projects manifested her primary artistic direction in the Amazonian cause. Her photographic documentation of oil fields and 40-year-old pipes that had simply been painted over rather than revised, countered the accusations made by state-owned oil suppliers (i.e. PetroPeru) that indigenous campaigners had sabotaged northern pipelines. Her protest painting series ‘Recuerda!’ (‘Remember!’) was based on a series of photographs published in the local newspaper ‘La República.’ She scanned, painted and printed copies of e.g. ‘Sin agua ni pescados’ (‘Without Water nor Fish’) and ‘Los menores de edad de Cuninico’ (‘The underaged workers of Cuninico’) to distribute across Lima and extend the longevity and impact of their exposure. Finally, her video performance ‘El Puma Negro’ (‘The Black Puma’) was a re-interpretation, and thus a translation, of an oral mythology that the native Cuninico community told their children. The story warned them not to shower themselves in the close-by Marañón river, because the black puma might come to devour them. In reality, the predator represented the thick muddy clots of black crude oil that had caused disease amongst the natives before. Not only prompting headaches, nausea, stomach aches and swellings, the toxic substance also polluted their food and life source; carpeting the local fishing lagoons with dead fish.

Helga’s artistic intuitions best come into fruition when working with paint. After all, she graduated from Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting in 2013. Particularly fond of Nogalina paint for its similarity in tone and shine to the petroleum polluting the riverbanks, she applied it recently to her ‘Apus’ painting series. The portraits depict contemporary (spiritual) heroes - the “Apus” - that have stood upright as native leaders throughout environmental protests. The young artist joins the new generation of “Amazonistas” - artists native to the region - in reversing the devaluation of local traditions and knowledge that had kept balance in the natural ecosystem for centuries.

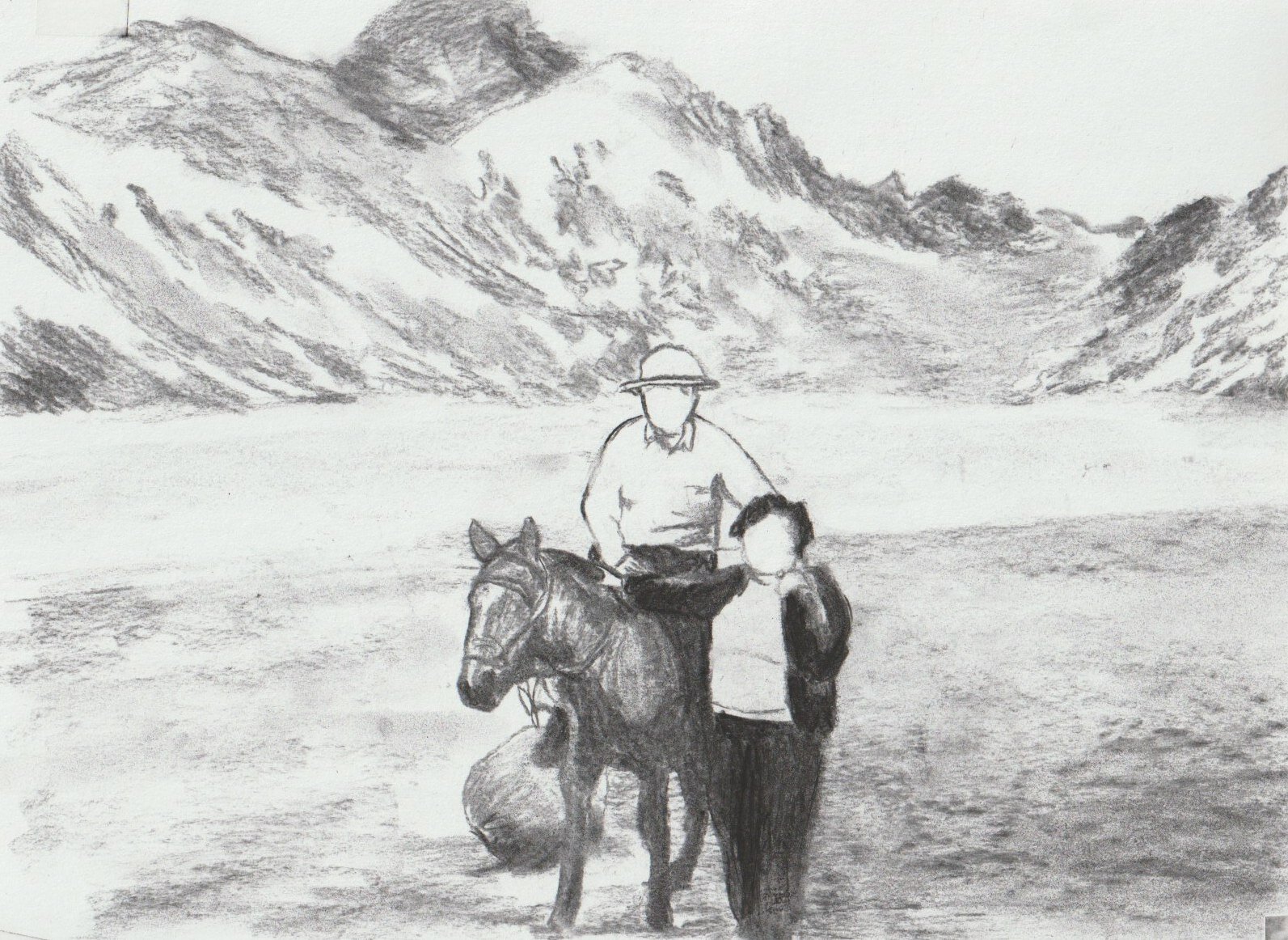

Contrary to Helga’s well-defined ties to the Amazonian traditions, her father’s ancestry is much more convoluted and difficult to trace. Her mother initiated the genealogical investigations 30 years ago, which the artist is complementing by requesting access to various local German archives e.g. Staatliche Museen, the Ethnographic Museum. Her timeline begins around 1925, when her great-grandfather migrating to Northern Peru, and ends a couple of decades later with Helga emigrating to Germany.

Along her search for answers, the artist was led to the mountainous region of Huaraz - also known as the Peruvian Switzerland. She rejoiced with distant relatives and pieced together photographs in order to align a family narrative that weathered bigger life events i.e. WWII, interoceanic trips, the 1970 Huaraz earthquake and the common cyclical events e.g. births, marriages, family reunions, illnesses and deaths. While Helga has been able to recreate a visual narrative through sketches, she describes the investigation process to have been thoroughly bureaucratic and therefore a “cold” and “distant” experience. The photographs have allowed her to relive stories of the past that are not entirely hers, but relevant enough to give her hope and to disappoint.

To compensate, the artist is eager to add warmth and colour to the narrative by creating a large-scale painting that will gather all of the collected imageries, documents, archives and passports . To Elsner Torres, art is a medium that should reflect a societal discourse that is accessible to all. “Wo kommst du her?” is thus not just a project that aims to close her inner family circle, but one that strives to spark an inkling of identification or connection in others. Helga is well-immersed into a growing community of international artists and friends, engages in the Berlin-based Peruvian initiative ‘MigrArte Perú’ and continuously produces artistic projects to polish a credible tone of voice that will offer an alternative migration story.

How do you connect to your ancestral lines?

Many Peruvian families have distant relatives or far-away roots in countries such as Japan, Italy, China, Spain, Germany, amongst others. How vividly have they allowed themselves to dream-up or investigate an alternative narrative rather than choosing to forget? In what ways ways could their sensibilities towards the past, present and future be challenge and inspired?

How much have you heard about the family stories of your closest friends and family?

Countries and continents will continue to face large influxes of immigrants. How will their stories and heritage be remembered? What can their narration reveal to us?

Where do you come from and how will you continue your narrative?

The search for meaning may not only conclude itself in our own stories, but in those that we share.