¡LUCHA Perú! Introducing the Peruvian Artivist Archive (AAP)

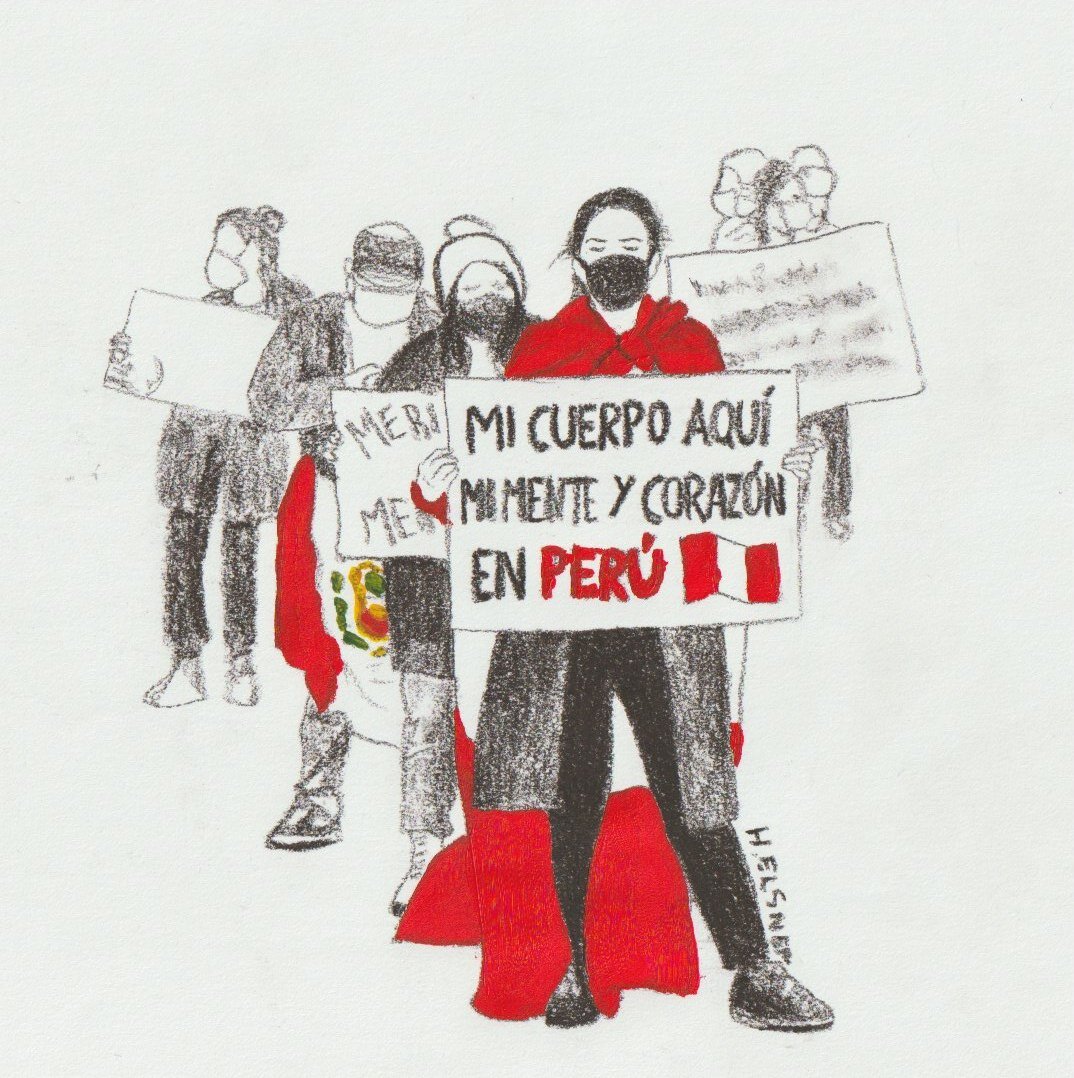

On November 9th, Peru woke up to a country without a president. “There are no words for what just happened in our country” read an Instagram publication on the BLOC Art account, “but (artist) Liliana Ávalos explains it well with this image #PeruIsGlitching” (see image below). Founder Brenda Lucia Ortiz Clarke was struck by the distress that zapped through the Peruvian population and had stimulated thousands of protestors to gather outside of Congress in Lima, Peru. Meanwhile, I sat locked-down in my apartment in Berlin, Germany. My eyes were locked to the screen. As Berlin-based Peruvian artist Helga Elsner Torres put it into simple words: “Mi cuerpo aquí, mi mente y corazón en Perú” (My body is here, my mind and heart in Peru).

“There are no words for what just happened in our country, but (artist) Liliana Ávalos explains it well with this image. #PeruIsGlitching”

- Brenda Lucia Ortiz Clarke

Image ‘Glitch’ by Liliana Ávalos ©Archivo Artivista Peruano

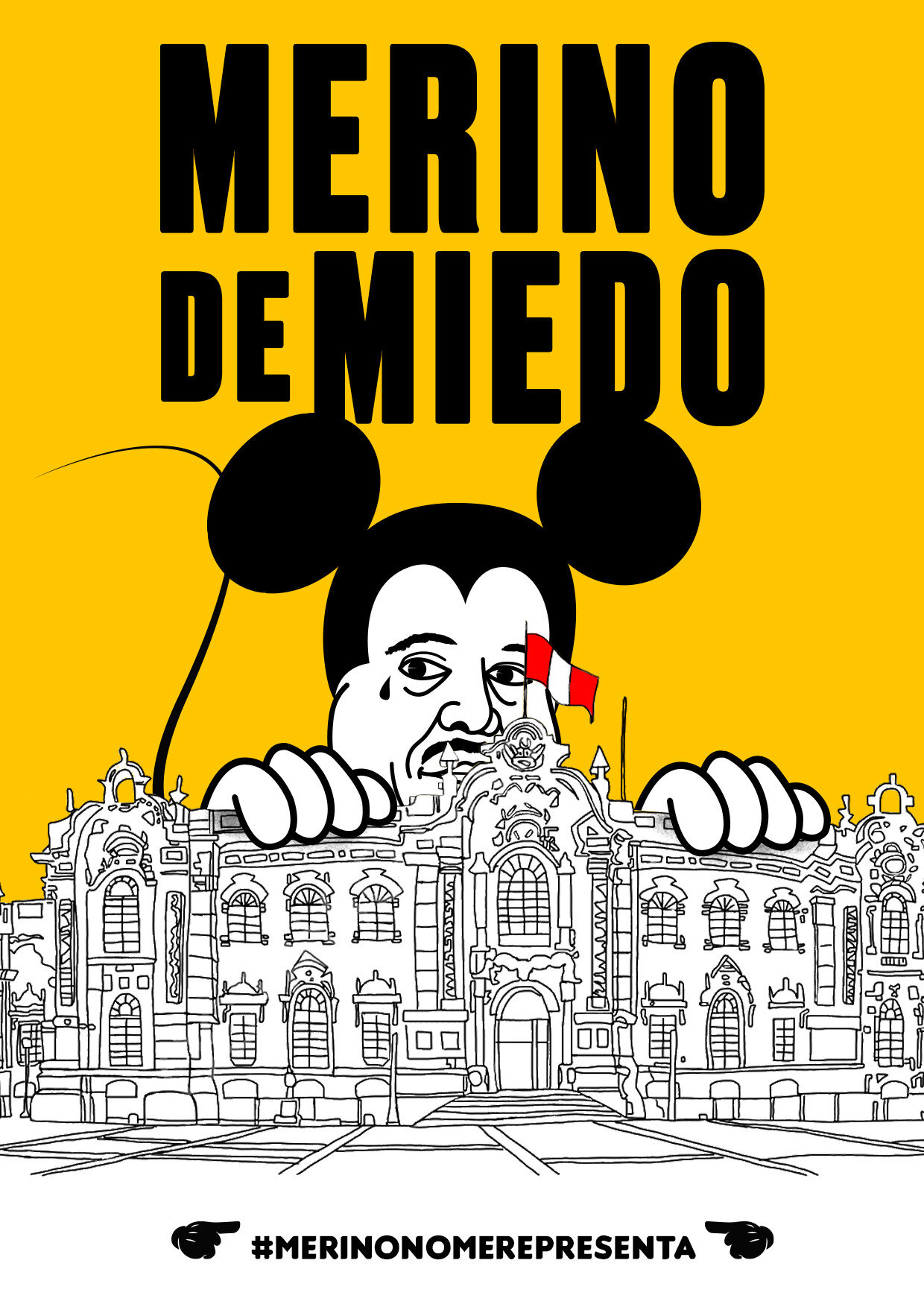

Former President Martín Vizcarra had been summoned that Monday morning to testify about his “moral incapacity” as a leader, shortly after which he was impeached without any further legal processes confirming or denying the accusation. Although he was widely favoured by the Peruvian population with 86% support, he was ousted with 105 (from 130) votes in Congress. Ironically, 60 of the participating deputies were under investigation for corruption charges themselves. Manuel Merino succeeded as de facto president the following day, to whom many citizens did not relate nor respond. #MerinoNoMeRepresenta (Merino does not represent me) was amongst the first slogans to express the widespread public contempt for the entire political class; Merino as the figurative punching bag.

Media channels and international press documented, and distorted, the events that would take place throughout the next week. While Peruvians are well accustomed to a twisted series of political lies and corruption, their civil right to vote had been violated. Rightfully so, they were angry and upset at a malfunctioning democracy that persistently abuses their livelihood. Taking it to the streets, they marched under the collective mantra “mi voz existe” (my voice exists).”

‘Mi Voz Existe’ by Cristina Flores (IG: @cristina.flores.pescoran) ©Archivo Artivista Peruano

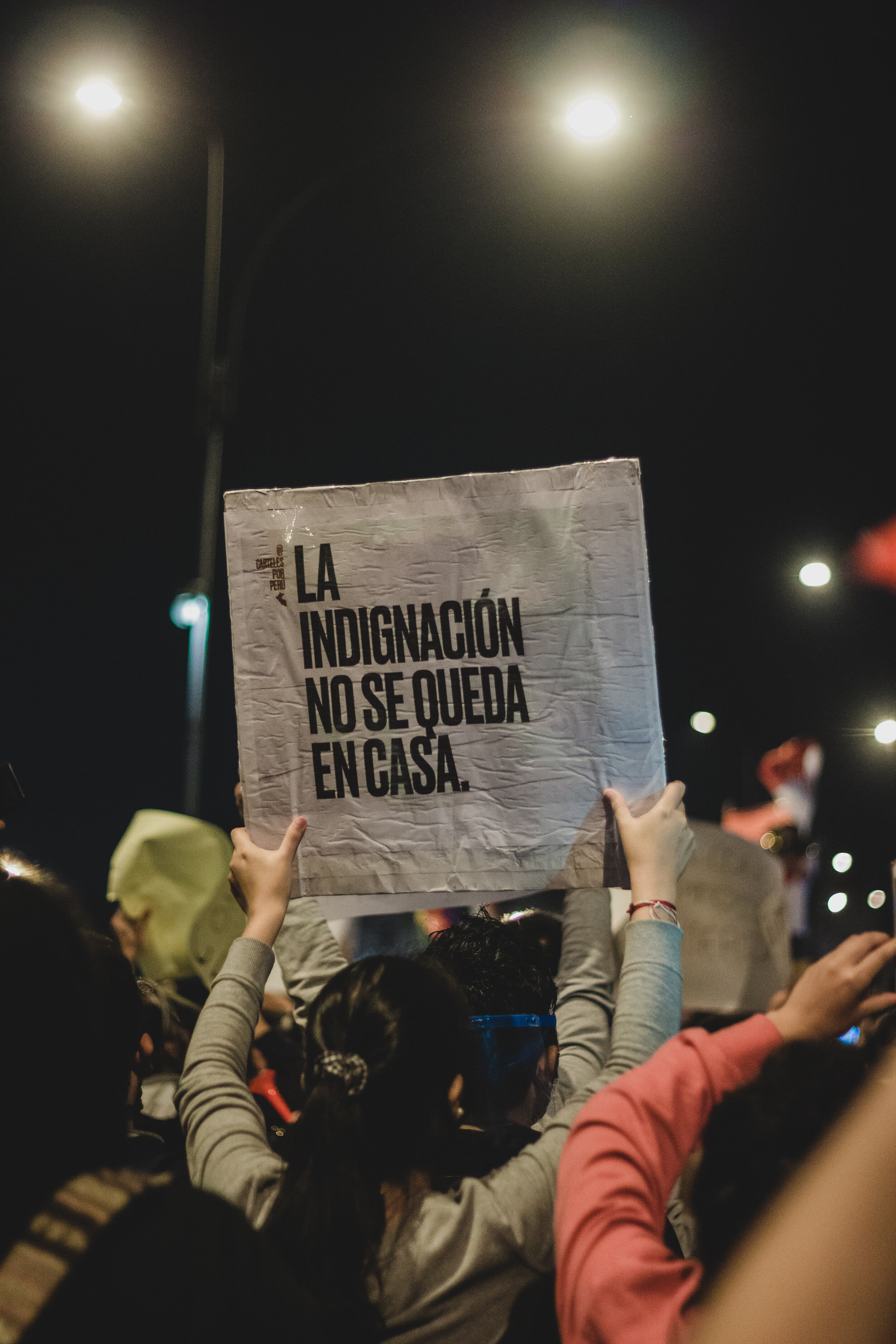

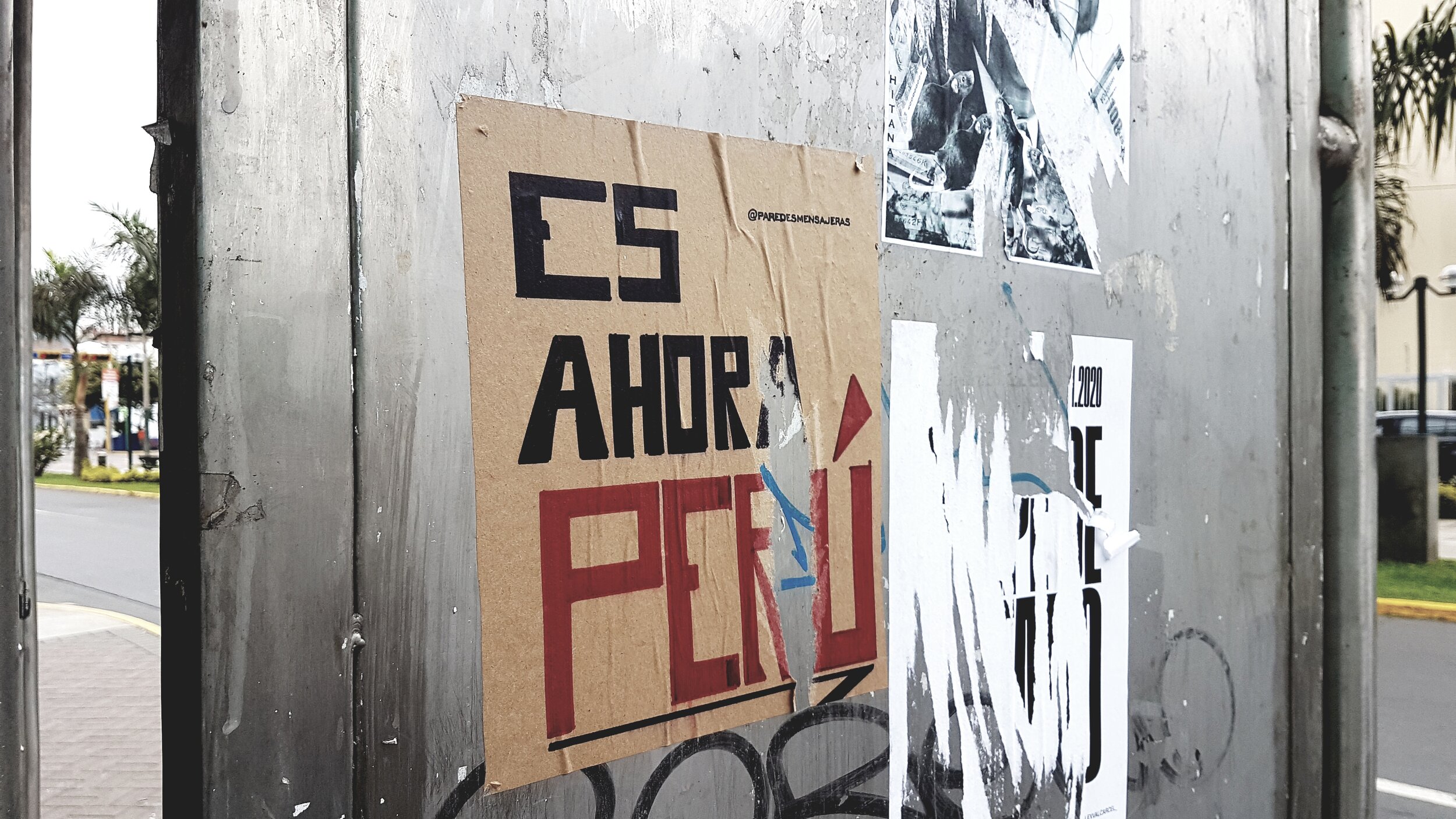

Some voices shouted into the waves of noise that echoed through the streets. Hitting their pots and their pans or holding up black inked cardboard signs, Peruvians across the country shook the streets. “Defender la democracia” (defend the democracy) and “La indignación no se queda en casa” (outrage doesn't stay at home) acknowledged the formation of their united front against the injustice faced. Some tied the national flag around their neck, some others waved it above their heads and some brought elongated versions that protestors could collectively hold onto as they walked side-by-side. The air above the country was thick, while uncertainty crept in the cities below: from the colonial city Arequipa to the Amazonian Iquitos, down to the Andean city Cuzco to the most northern coastal city Tumbes. Even half-way around the globe, Peruvian communities gathered in public squares (e.g. Spain, United Kingdom, Germany) as a way to voice their homage away from home.

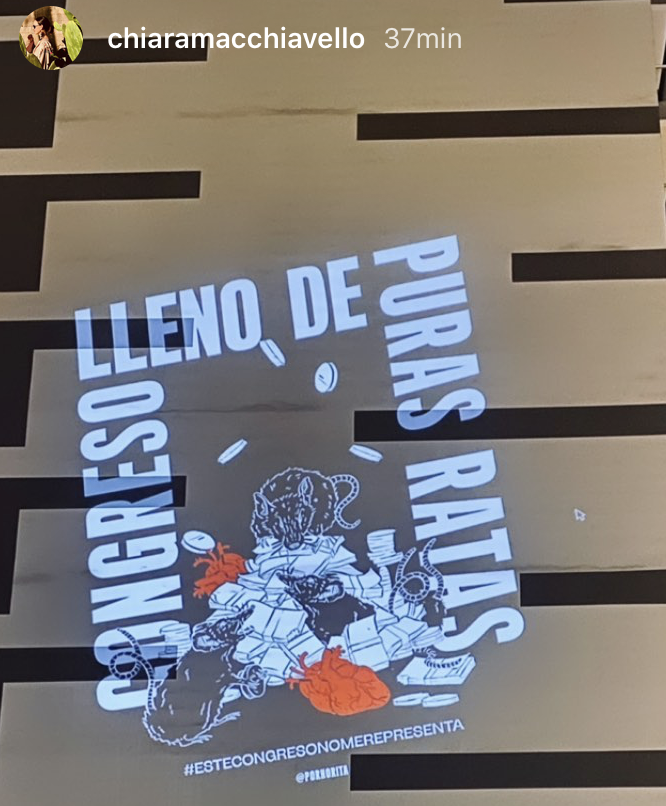

Other voices were more discreet; creative, conversational and organisational. Commentaries such as “Merino eres el atraso” (Merino, you are the backward one) or graphic designs such as “Congreso lleno de puras ratas” (The congress is full of pure rats) were projected onto Limenian multi-family residential buildings to be publicly seen. Otherwise drawings, paintings, poems, songs and other forms of cultural expressions streamed through the digital portals straight onto our screens. With a few clicks and swipes, the hashtag network could be navigated for an array of impressions that aligned the collective memory as one. Yet, it was not organised as one.

At this point, BLOC Art Founder Brenda Lucia Ortiz Clarke made an open call-to-action to alert the glocal Peruvian art community to come together “as a cultural front against the coup.” She comments:

“A lot of the artists were expressing their gratitude for being a part of something structured when sending us their proposals. They were simply responding to a call and had underestimated the power of a collective. But what better way to unite than through art? We can move together and not feel that we are alone in this, because we are not. We are courageous for doing this - every single one of the artists and cultural agents who decided to join.”

Within our community BLOC Art is well known to favour ‘artivists,’ an acronym that alludes to the combination of the words ‘activism’ and ‘artist.’ In light of that theme, many of the weekly ‘Artsy Sunday’ IGTV episodes with the American ‘Queen of Hearts Foundation’ (IG: @queenofheartsglobal) have focused on the “power of art” in protests and the streets to create community identity and movement. During one of their open conversations, Brenda and her collaborator Rachel motivated their live viewers to ask themselves:

“what am I doing from my comfort zone to connect with others and create a sustainable long-term community mindset?”

This frame of mind she attributes to the Latin American art community. Inspired by the ethics of cultural agents and gallerists in the region, Brenda uses the BLOC Art platform as a mechanism to talk directly to- and with the local community. Now she has gathered more than 100 artistic documents that testify to the perspectives, facts and expressions of this particular moment in Peruvian history. BLOC Art Peru is proud to introduce the ‘Archivo Artivista Peruano’ (AAP)!

It is the first Peruvian Artivist Archive with explicit social content and a curatorial text written by Cuban curator Daniel G. Alfonso:

“You will see art expressions from not just different parts of the world but regions of Peru, demonstrating the local art scene as one that is decentralised. With it, it is safe to say that there are cultural expressions from the entire country and not just the capital, as typically communicated. It certainly does not bring a long-term solution, but it does document the importance and power of art from the Peruvian perspective.”

- Brenda Lucia Ortiz Clarke (BLOC)

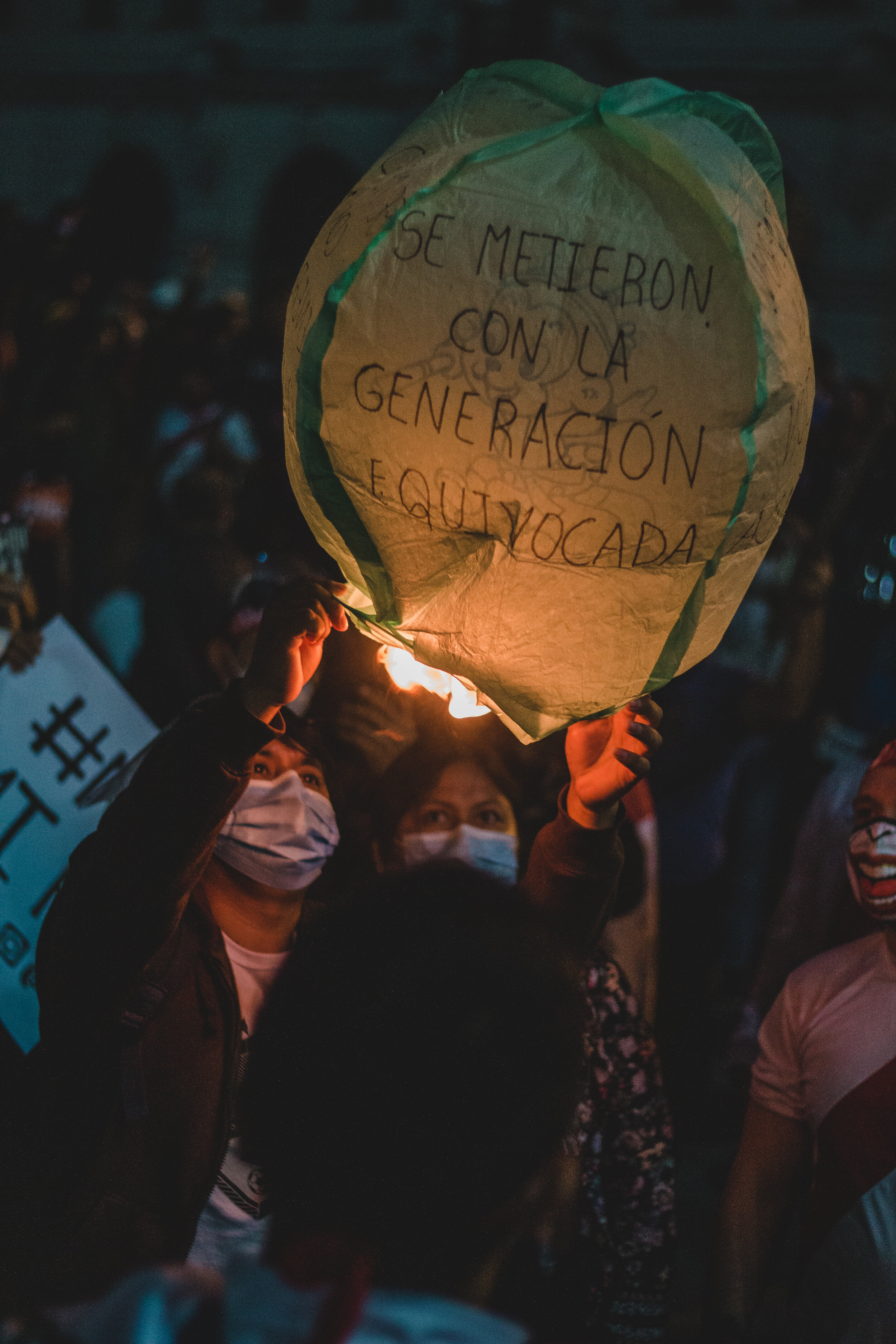

The featured documents speak for the ‘Generación del Bicentenario’ (Bicentennial Generation), the praised younger electorate that demands profound changes. A balloon brought afloat, stating “se metieron con la generación equivocada,” sends a clear message to Peruvian congress: you have messed with the wrong generation! Yet, like many political systems around the world, the Peruvian landscape is rotten to its core and the road to improvement is long.

Here are the facts:

Peru’s democracy has been described as “defective” in the Bertelsman Transformation Index and ranks in the lower-mid range on the scale for democratic constitutionality of states. All elected presidents since 2001 have either been convicted for corruption or accused of it in preliminary proceedings. The landscape is fragmented, consisting of presidential personalities and party platforms that seek success through one another or through the creation of new ones. Of the 24 “parties” that ran during the last legislative elections, only 12 are currently represented in congress and most have only regional significance. As a result, majorities and coalitions form mostly on a case-by-case basis (as seen with the impeachment of Vizcarra).

The fragmentation will continue. The question is rather, whether presidential candidates will once again succeed in fishing for populist votes with a neoliberal economic policy. While it has procured Peru as one of the fastest growing countries in the Latin American region, it has also caused the country to suffer from high poverty rates and increased social conflicts - which has become all the more evident as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis. Elementary public services are lacking. Basic health care spending is limited and state presence in the countryside, as to curb illegal (mining) activities and to compensate for the resulting social disadvantages, is lacking.

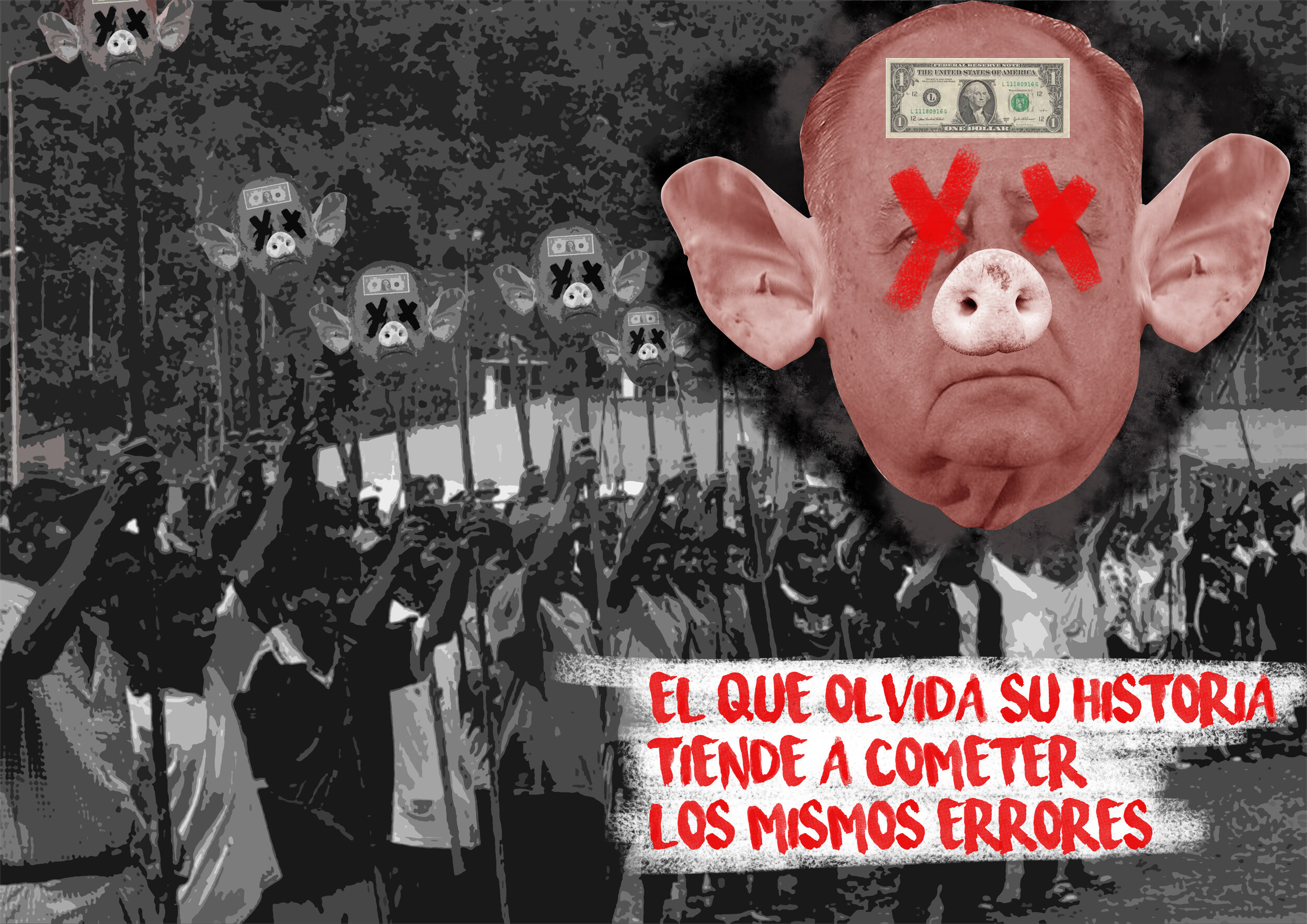

The cardboard signs put it correctly then. Assertions, such as “El congreso es la pandemia que nunca termina #EsteCongresoNoMeRepresenta” (The Congress is the pandemic that never finishes #ThisCongressDoesNotRepresentMe) and “Quiero congresistas que me representen y no que me roben” (I want congressmen to represent me and not to steal from me) are directly linked to the semiotic references made to rats, nibbling away on the vitality of the Peruvian state. 15% of all public spending flows directly into the pockets of corrupt politicians, which can largely be explained by the fact that 70% of the public sector is informal. The video animation by Marysol Nanfuñay even re-plays live recordings of congress- men and women blatantly admitting corruption: “…seguir trabajando en favor de la corrupción” (…continue to work in favour of corruption) and “por dios, por la plat…(plata) patria” (for god, for the mon…(money) fatherland). Thereafter, Artist Ziad Ali Yassin’s graphic piece remind us of the 2009 ‘Baguazo’ social conflict that had involved Prime Minister Ántero Flores Aráoz as a warning: “El que olvida su historia tiende a cometer los mismos errores” (He who forgets his history tends to make the same mistakes).

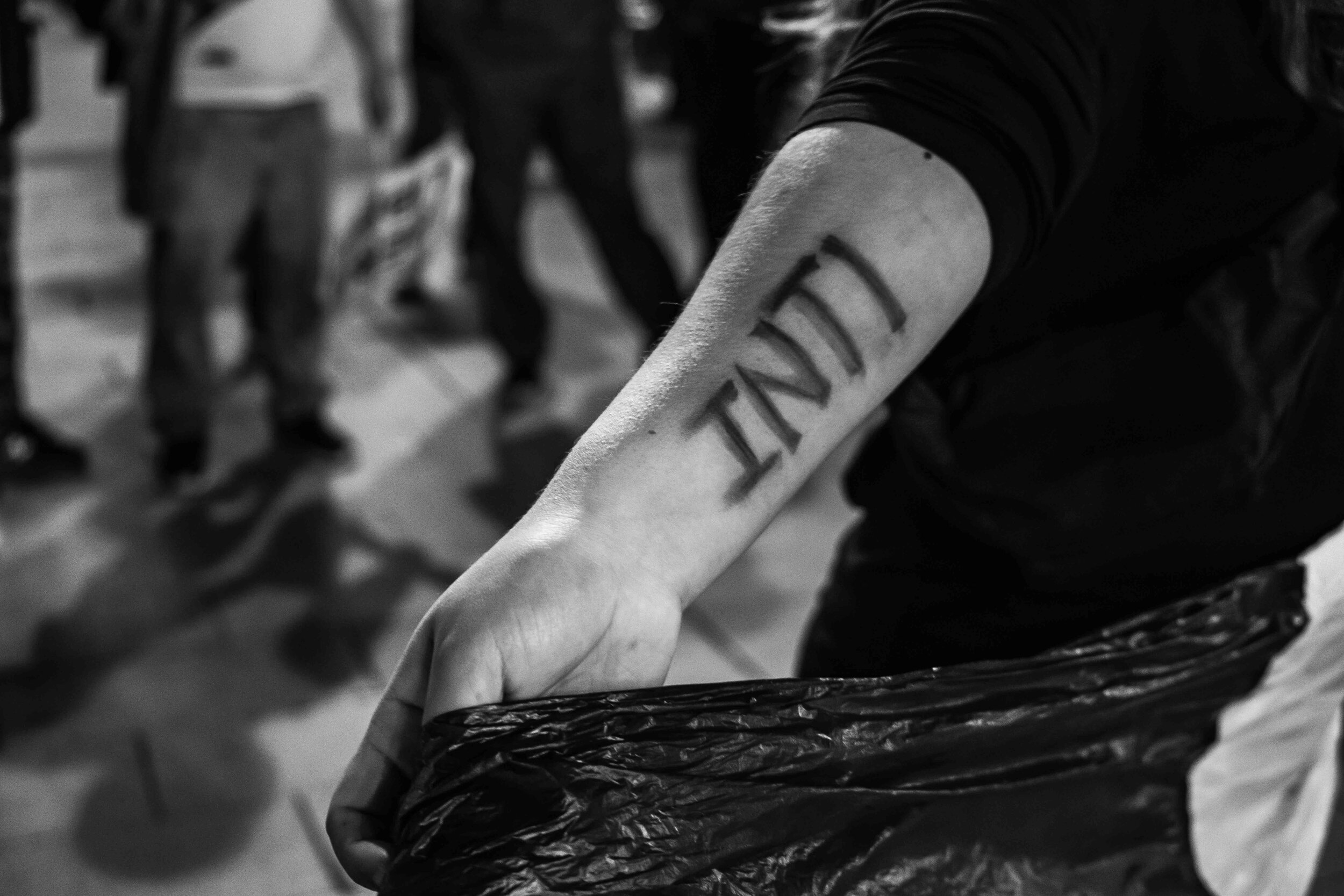

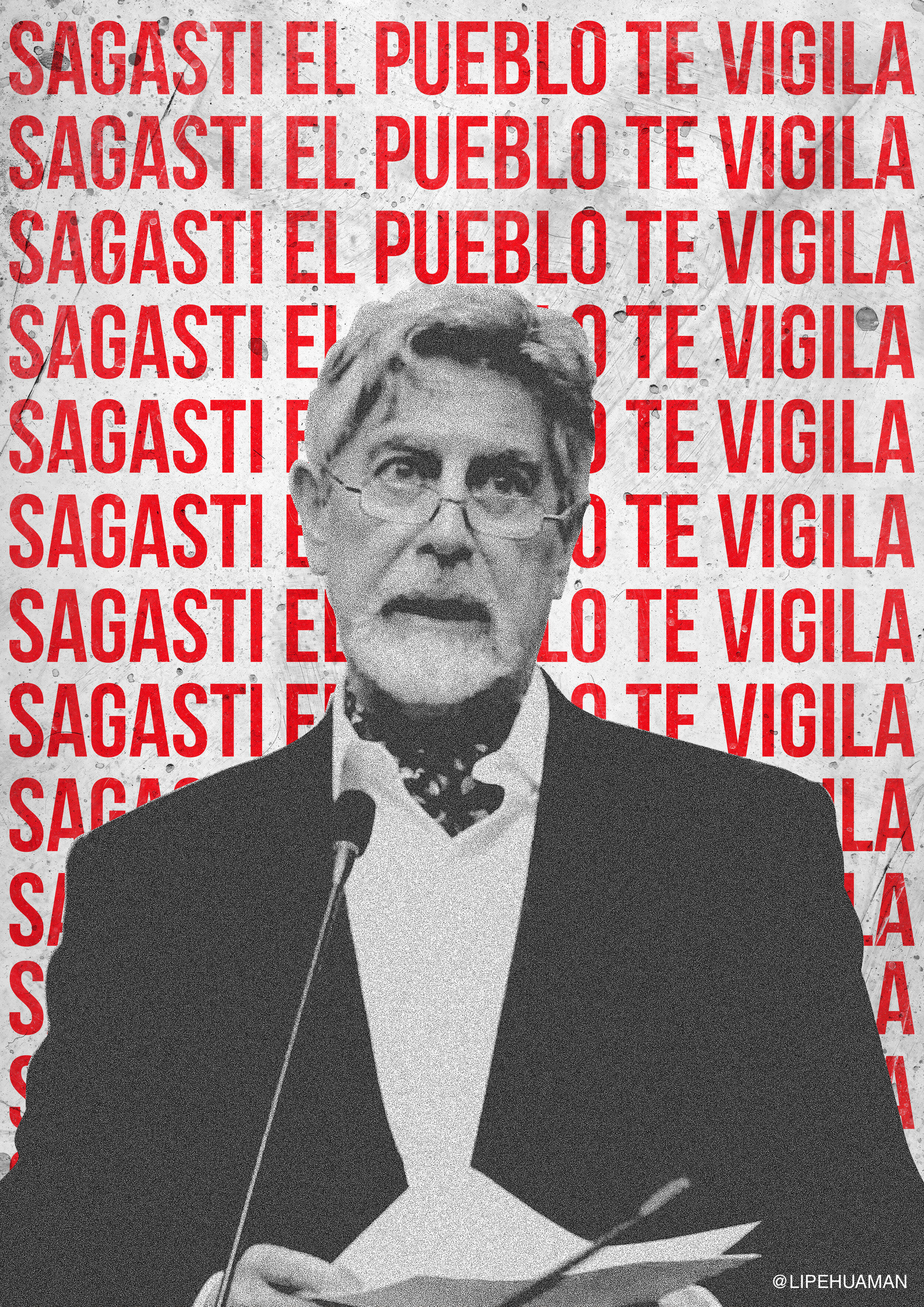

On November 14th, the protests had already begun to escalate. Tear gas and rubber bullets were shot into crowds and two young protestors died, 22-year-old Jack Brian Pintado Sánchez and 24-year-old Jordan Inti Sotelo Camargo. What followed was the resignation of eleven ministers and, on November 15th, that of Manuel Merino. In the evening hours, the protestors marched in sadness. They demanded a new constitution and justice for those that had disappeared or were killed and injured unnecessarily. The following day, Francisco Sagasti was inaugurated as interim president. His first act was to dedicate a minute of silence in tribute to the young protesters who had died, Bryan and Inti.

Sagasti will be in power until the next presidential elections in April, 2021. The (felt) demand for a new constitution has reduced. Meanwhile, some presidential candidates are proposing referendums despite an errant parliament and current political polarisation. Such a change would need to be preceded by an agreement on its content. The Constitutional Court has yet to agree on and comment on the notion of “moral incapacity,” based on which Martín Vizcarra was impeached in the first place.

The illegitimate activities of congress have become the emblem for the protests. Current parliament reputation lies at an all-time low, with just 12% approval.

What the marches have demonstrated is that the Generación del Bicentenario is in favour of a democracy and that, it too, can act and penalise politicians for their actions. The Archivo Artivista Peruano is a platform that speaks for- and with- the community. As curator Daniel G. Alfonso concludes: the contributing artists have formulated a visible and feasible cultural voice that marks this moment in Peruvian history. We invite you to have a look at the full archive, to tweak your critical thinking and not to settle.

¡Lucha Perú! Es ahora! we say. (Fight, Peru! The time is now!)